Arizona state historian Marshall Trimble on the westernmost battle of the Civil War

Arizona state historian Marshall Trimble on the westernmost battle of the Civil War.

By Marshall Trimble

For a brief time in early 1862, cavalry troops from the Texas Confederate Army occupied Arizona. This was part of a grand Confederate plan to occupy New Mexico and open a path to California. The so-called westernmost battle of the Civil War was fought here on April 15, 1862, when Union cavalry, traveling east from California, clashed with Confederate soldiers at Picacho Peak on the Gila Trail. Casualties were light; the Union lost three men, while the Confederates lost two.

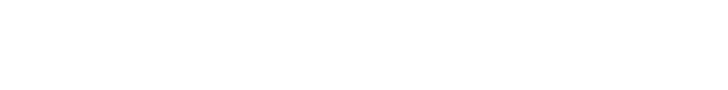

This rugged 3,374-foot-high peak, a tilted remnant of ancient lava flows, was also a stage station for the storied Butterfield-Overland Stage Line and marked the halfway point between Tucson and the Gila River. The peak has long served as a landmark for Indians, Spanish explorers, mountain men emigrants, and American soldiers traveling along the Gila Trail. Springs located on the slopes of the mountains made it an important stop for thirsty travelers.

The Confederate occupation of Arizona began a few weeks earlier when Captain Sherod Hunter and his Arizona Rangers, numbering some 54 to100 men, rode into Tucson on Feb. 28, 1862.

On March 3, Lt. Jack Swilling led Hunter and his men to Sacaton where the Confederate commander launched a brilliant guerilla-style hit and run campaign capturing and destroying food, supplies, and hay that was being stored for the 2300 Union California Column.

On March 10, Hunter cleverly captured 11 Yanks at Ami White’s flourmill at the Pima Villages at today’s Sacaton. A few days later, on March 30, there was a skirmish at Stanwix Station on the Gila where one union soldier was wounded.

April 16, 1862, Lieutenant James Barrett and 12 men, along with a scout named John Jones, rode into the pass at Picacho and captured three Rebels. Seven other Rebs hiding in the brush opened fire, killing three and wounding three more. A 20-minunte firefight ensued. It’s said 24 men on both sides were engaged and casualties numbered 11.

Afterward, Hunter, realizing he was far outnumbered, evacuated Tucson and headed east towards Texas.

Neither Hunter nor Lt. Jim Tevis, who rode up to Picacho after the fight to get details, reported any killed or wounded. Both were always honest in their reports and didn’t try to hide anything, so it’s likely none were wounded or killed. They reported three captured and that’s all.

There was no surviving muster roll and only 67 of Hunter’s Rangers are known. About half were Texan and the rest from New Mexico. Hunter was so clever with his tactics; Union General James Carleton thought he had at least 800 men.

The Union sent scout John W. Jones into Tucson to spy. Hunter was suspicious, but after making him swear an allegiance to the Confederacy, he released him. Jones was not supposed to go back to the Gila Trail but he headed south towards Mexico then cut across Camino Del Diablo and returned to Yuma and gave the Union the size of Hunter’s small force. California newspapers were claiming there were thousands of Rebels in Tucson preparing to invade their state.

Still, the plodding Union force was moving so slow, the old scout Paulino Weaver got fed up and quit at Sacaton saying, “If you fellers can’t find the road to Tucson from here you can go to hell.”

A year later while leading a band of prospectors up the Hassayampa River, the Weaver-Peeples Party struck gold at Rich Hill. It was the richest placer gold discovery in Arizona history.

Related posts

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.