Cornish Miners and Tommyknockers

Cornish Miners and Tommyknockers

The perils of gold mining led to the stuff of legends––some real and some imagined.

By Marshall Trimble

The rocky wilderness of the American West turned out to be the richest treasure trove of natural resources in the history of the civilized world. And the chance to get rich quick as a uniquely American article of faith was virtually born in the West.

With a single lucky break, one could instantly make as much money as he could lend or spend in a lifetime. For the first time in history the finder got to keep what he found.

The first gold strikes in Arizona occurred in the late 1850s and early 1860s along the Gila and Colorado Rivers. In 1863 Jack Swilling led the Walker party up the Hassayampa River and found gold in the area where Prescott is today. They were closely followed by the Weaver-Peeples party and Henry Wickenburg who struck it rich around where the town named for Henry was established. The 1860s are regarded as the age of the placer gold strikes in Arizona.

Placer gold, the kind you could mine with the toe or your boot, or a jackknife soon played out and the romantic day of the jackass prospector evolved into the era of the hard-rock miner.

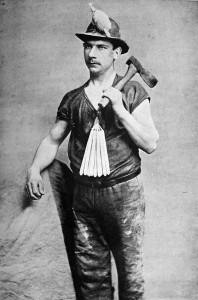

In the early days of underground mining highly skilled Cornish miners with their unusual language and brogue were imported to do the work. At the time they led the world in mining technology and were regarded as the greatest hard rock miners in the world. This close-knit band of miners and their wives were known as “Cousin Jacks” and “Cousin Jennies,” The name is supposed to come from their habit of addressing one another as “cousin” and Jack was a common Cornish name. Others say it was because they were always asking for a job for their cousin Jack back in Cornwall.

During the mid-19th century the tin and copper industry in Cornwall was in steep decline and the miners were well aware of the gold, silver, and copper mines that were booming all over the American West. America welcomed over a quarter of a million Cornish immigrants, or some 20 percent of their population, between 1860 and 1900.

Mining was hard, dangerous work where death was a constant companion. Before caged elevators came into use, miners were lowered hundreds of feet into the murky depths in a big steel bucket powered by a “burro engine,” which lowered the bucket on a long cable. A broken cable could send helpless miners tumbling hundreds of feet to their death. Cave-ins trapped them causing a slow death. The poisonous gasses that drifted through the tunnels were a silent killer. Since canaries couldn’t live long in the foul air, miners brought them down into the mines. When the bird died it was time to make a hasty exit. Rats also had a keen sense of danger. Like leaving a sinking ship, “when the rats turned tail, so did the miner.”

Mules could be prophetic. One time a mule headed out of the tunnel before the ore car was filled and when the miner went out to retrieve the animal the tunnel collapsed. The strike from a miners pick might open up a cavern of scalding water. Fires were common and the thing miners feared the most. When a miner started his shift, he never knew for certain if the day might be his last.

Men who work where danger is a way of life have a tendency to embrace superstitions or habits that might seem strange to an outsider. For example, miners believed it was bad luck for a woman to go into a mine. If a man’s clothes slipped off the hook in the change room he was going to fall off into a hole. Or, if a man’s lamp didn’t burn bright underground it meant above ground his wife was stepping out with another man.

The most unusual of the Cornish miner’s superstitions were the “Tommyknockers.” These were mischievous little people who stood only two feet tall, had big heads, long arms, wrinkled faces, and white whiskers. It was said the little sprites sneaked into the luggage of the Cornishmen as they left for America. Once here, they infiltrated the mines by hiding in the miner’s lunch boxes. It was claimed the Tommyknockers communicated with miners by tapping on the walls with a code similar to the one devised by Samuel Morse. Sometimes these tapings warned of pending disaster, while others gave directions to rich pockets of ore. Many a hard rock miner swore his life was saved only because he heeded the tapping of the little people and made a hasty exit from the mine. Tommyknockers were credited with locating many a bonanza. But it was vitally important to listen to the tommyknocks. Miners claimed that if one heard “tap tap,” it meant “Dig here!” or “That’s it,” whereas “Tap tap tap” meant “Don’t dig here” or “It ain’t here!”

Gassy Thompson was one of those Cornishmen who benefitted from the Tommyknockers. His two assistants were a dog aptly named Digby and a diamondback rattlesnake. He trained the dog to do the digging and came upon a baby rattler that had been orphaned and took it home and made a pet out of it. As the snake grew he noticed the population of pesky rats and mice diminished. He also figured that since the snake was much closer to the ground it could spot the gold nuggets he missed. So, he trained the big fellow to recognize gold. Whenever the snake found a nugget it would coil up around it and start rattling. Gassy claimed on one occasion the rattler found a pocket of gold worth almost $3,000.

During the hot summers Gassy would search for gold in the cool confines of the abandoned gold mines. There he learned to communicate with the Tommyknockers and they would tell him where to look for gold. Then Digby would do the manual labor.

There were skeptics who were prone to doubt Gassy’s method of finding gold but one thing is certain—according to the claims of local merchants, he always found more rich pockets of gold than all the other desert rats combined.

Related posts

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.