Route 66: America’s storied highway

State historian Marshall Trimble on America’s storied highway in its heyday.

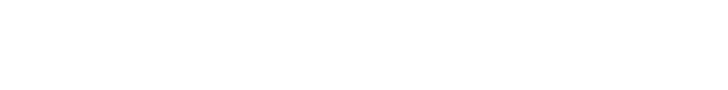

Of all America’s great highways, none epitomized Americana during the 20th century more than storied Route 66. Stretching across the heart of the country from Chicago to Los Angeles, it rambled nearly 2,500 miles through Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. Route 66 has inspired writers, poets, songwriters, artists, and photographers. It was the 20th century’s rendition of the Golden Road to the Promised Land—the Gila Trail, Beale Camel Road, Oregon Trail, California Trail, and the Yellow Brick Road all rolled into one.

The highway was born in the 1850s as a wagon road. It was surveyed along the 35th Parallel in 1857–1858 by Lt. Ned Beale of the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers and his amazing camels. At a cost of $210,000 the Beale Camel Road was the first federally funded road in the Southwest. In 1912 it morphed into the National Old Trails Highway, also known as the Ocean to Ocean Highway. It became Route 66 on Nov. 11, 1926, one of the original federal routes in the U.S. Highway system.

For the first time in history, American families could take to the road as tourists. The wondrous wonders of the West beckoned; real Indians selling their exquisite woven blankets, fine pottery, silver/turquoise jewelry; prehistoric native ruins and cliff dwellings, dating back more than a thousand years ago; zoos with rattlesnakes and mountain lions; painted deserts, petrified forests, towering snow-capped mountains, the best-preserved meteor on earth that struck the high desert 50,000 years ago; and the grandest canyon of them all.

The 1930s Great Depression slowed things down a bit, followed by gas rationing during World War II but by the late 1940s they were ready to hit the road again.

I was 8 years old in 1947 when our family left Phoenix and headed north to Prescott on a dusty, dirt road known as the Black Canyon Highway. Our final destination was a little town on Route 66 called Ash Fork. It took us more than a week to get there. We’d have arrived sooner if the car hadn’t broken down, stranding us for several days at Bumble Bee and the old stagecoach station Cordes.

My father had recently hired out for the Santa Fe Railroad and we would reside in Ash Fork for the next eight years. Almost half of those years were spent living in a two-room trailer with no plumbing. It was so small you couldn’t cuss out a cat without gettin’ hair in your mouth.

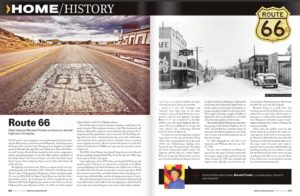

Small as it was, the “entering” and “leaving” town signs were on the same telephone pole, and Ash Fork was an important railroad and highway junction. Before I-17 was completed in the late 1960s it was the main highway link between Phoenix and Route 66. It was the only railroad line connecting Phoenix with the Santa Fe Railroad.

I worked my way through high school at a gas station on the east end of town. Many of the folks traveling Route 66 in the early 1950s were Oklahomans heading west, bound for the “Promised Land.” For them the Great Depression hadn’t ended. The highway offered hope for a better future. I’ll never forget the forlorn faces on those poor families pulling into the gas station in an old car with several hungry-looking kids in the back seat. Sometimes they’d want to hock a radio or some piece of furniture to get gas enough to make it to the next town. They might only have a couple of dollars. I figured the boss could afford it so I would put a few extra gallons in their tanks.

The death knell for Route 66 came with the passing of the Federal Highway Act of 1956. It provided for a national system of interstate and defense highways to be built over 13 years and would change the face of America forever.

In 1968, Flagstaff was the first to be bypassed and Williams the last, on Oct. 13, 1984.

Its days were numbered and Route 66 passed into the pages of history along with the wagons, stagecoaches, and even camels when, on June 27, 1985, the venerable old highway was officially removed from the United States Highway System. But Route 66 didn’t die; you can’t kill a legend.

Between living in a small town and traveling up and down Route 66 in a small school bus to play high school sports in tiny gyms or rocky, wind-swept ballfields from Kingman to Sanders, I got to experience firsthand the culture of Route 66 during its heyday.

Those were the golden years for the Mother Road. It was before the towns became generic. Each had its own personality. Route 66 didn’t skirt the towns like the freeways of today but headed boldly down the main street of nearly every town it passed. I used to say you could blindfold me and drop me off in any one of them. I could lift the blind and look at the mom and pop storefronts and tell you in a second where I was. Those years remain foremost among my most cherished memories.

Related posts

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.